Is your language making you fat?

Yale professor claims how healthy or wealthy you are depends on your mother tongue, but does the argument have legs?

An American professor may have discovered why Russia has a problem with alcoholism. His study also suggests the English language is the reason for the abysmally low savings rate in English speaking countries. M. Keith Chen, an associate professor of economics at Yale University, says language affects how you form healthy habits – from diet and exercise to how much money you will save for retirement.

Chen’s study, The Effect of Language on Economic Behaviour, divides languages into two categories. Languages like Russian, English and Tamil that have strong future tense reference (FTR) force their speakers to differentiate present and future events. On the other hand, languages such as German, Japanese, Finnish and Mandarin with weak FTR blur the present and future.

For example, a German speaker predicting rain can naturally do so in the present tense, saying: “Morgen regnet es” which translates to “It rains tomorrow”.

In contrast, English would require the use of a future marker ‘will’ or ‘is going to’, as in “It will rain tomorrow”. Similarly, a Russian will say, “zavtra budyet dozhd”, where ‘budyet’ translates to ‘will’.

Basically, English and Russian have a distinction between present and future events that

German, Mandarin and Japanese do not.

Language impacts your bottomline, and your waistline

The study says weak-FTR speakers are 30 percent more likely to have saved in any given year, and have accumulated an additional $222,000 by retirement. He also finds that by retirement, weak-FTR speakers are in better health by numerous measures: they are 24 percent less likely to have smoked heavily, are 29 percent more likely to be physically active, and are 13 percent less likely to be medically obese.

“Speakers of weak FTR languages save more, hold more retirement wealth, smoke less, are less likely to be obese, and enjoy better long-run health,” says Chen. “This is true in every major region of the world.”

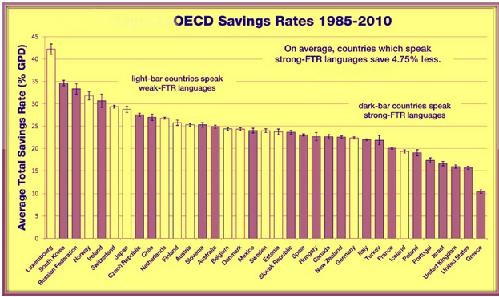

Chart shows average total OECD savings rates, accounting for both private and government consumption. Photo credit YALE

How it works

The study concludes that having a separate verb tense for your future self might make your future self a little harder to relate to. In strong FTR languages people are slightly nudged every time they speak, to think about the future as something viscerally different from the present. Since the future seems distant, they will be less willing to take up fewer future-oriented actions.

Basically, a habit of speech to treat the present and future as distinct can lead to a habit of mind that discounts future rewards and risks. People will be less willing to save in the present for the future. They might postpone fitness plans or continue to gorge on unhealthy food because a heart attack is years or decades away.

On the other hand, weak-FTR language speakers engage in much more future-oriented behavior. In Mandarin the present and future are the same. The upshot: the Chinese save like there is, well, no tomorrow.

No cultural connection

But are these correlations derived from cultural values or national traits that are coincident with language differences? Since the future zone (Germanic, Scandinavian and Finno-Ugric) is where the super savers live, could there be a Germanic cultural value towards savings that is widely held by Germanic-language speakers but not directly caused by language?

Well, the study also taps into the World Values Survey 2009 which asked respondents about their savings behaviour, the language which they speak at home, and the degree to which “thrift is an important value to teach children”.

According to the Survey, a language’s FTR is almost entirely uncorrelated with its speakers’ stated values towards savings. This suggests that the language effects operate through a channel which is independent of conscious attitudes towards savings.

OECD overview

Chen also looks at the national savings rates of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries to back up his study. He says countries with weak-FTR languages save more of their GDP per year than their strong-FTR counterparts.

This finding reverses the long-standing pattern of northern-European countries saving more that their southern counterparts. While it is true that northern-European countries tend to save more, northern-Europeans also tend to speak weak-FTR languages. Once the effect of language is accounted for, the effect of Latitude flips; within language classes northern-European countries actually save less than their southern counterparts. So, the study avers, what has been commonly thought of as a north-versus-south divide in European savings rates may actually be more fully explained by language.

Linguists disagree

While Chen’s hypothesis holds up under European conditions, he doesn’t fully factor in Indian languages – perhaps because of their spoiler effect. Indians are some of the world’s most tenacious savers, and yet several Indian languages show strong as well as weak-FTR characteristics. For instance, a Hindi speaker might say, “Ladayi kal ho rahi hai” to mean “The fight takes place tomorrow”; this is just as grammatically correct as “Ladayi kal hogi” which translates into “The fight will happen tomorrow”. Such examples are common in many other Indian languages.

Even your uppity London landlord wouldn’t mind if you tell him “I pay you tomorrow” rather than “I will pay you tomorrow”. And Chinese speakers are vehement that their language has elements of future tense.

What about people who speak more than one language? Many Indians speak three or four languages – of the strong-FTR drift – and yet the Indian appetite for savings instruments like gold is insatiable.

Asya Pereltsvaig, who teaches at Stanford’s Department of Linguistics is dismissive of the study. She says in her blog that the Yale professor has wrongly classified Russian as a strong-WTR language. “In Russian I can use ‘Ya ushla’, literally ‘I left’ when I am about to leave,” she writes.

Viveka Velupillai and Östen Dahl of the World Atlas of Language Structures point out: “It is relatively rare for a language to totally lack any grammatical means for marking the future. Most languages have at least one or more weakly grammaticalised devices for doing so.”

If anything, Chen’s paper offers a good example of why economists have so much trouble predicting the future.

Chen’s work hasn’t yet passed the most crucial test of research – peer review. Until then stop blaming your mother tongue for having insufficient funds in your savings account. Or for not being able to kick your vodka addition.

This story was first published at www.indrus.in

(About the author: Rakesh Krishnan Simha is a New Zealand based writer and a columnist with Russia Behind the Headlines. He has previously worked with Businessworld, India Today and Hindustan Times, and was news editor with the Financial Express.)