By agreeing to examine the validity of the Bodhgaya Temple Act, 1949, to nullify Hindu control over the famed vihara, the Supreme Court has inadvertently exposed The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, to scrutiny and opened the door for Hindu claims to historical temples they have demanded for centuries.

The Narasimha Rao regime passed the 1991 Act to prohibit any change in the character of any place of worship as it existed on 15 August, 1947, and thus freeze disputes over religious sites seized during the medieval ages, whose restitution was being demanded by the Hindu community. The Babri Masjid was excluded from the Act’s purview as it was sub-judice.

By admitting the plea on the Mahabodhi temple, the bench has taken a narrow view of the oceanic nature of native Indian tradition. In the 1920s itself, renowned archaeologist R.P. Chanda noted the Indus roots of Yogic tradition (possibly India’s most significant spiritual dimension), particularly the meditation forms that came to be associated with Bauddha and Jaina practice. He observed that the discoveries at Indus sites show that both traditions are indebted to the Indus civilization for some of their cardinal ideas. Scholars now believe that what were later identified as distinct Hindu, Jaina and Bauddha spiritual streams, had common roots in the Indus civilisation.

Prince Siddhartha (6th century BC) said there had been many Buddhas before him; Buddhist theology has rich genealogies of past Buddhas and the previous lives of Sakya Muni. Bodhgaya is where Gautama attained Enlightenment in this yuga; Emperor Ashoka commemorated the site with the Vajrasana (Diamond Throne) in the 3rd century BC. Asoka also erected a stupa, which was reconstructed as the Mahabodhi Mahavihara by Gupta kings in the 7th century AD. In the 13th century, the Mahavihara was sacked by the Turks; the Bhikshus massacred or scattered, and the site abandoned.

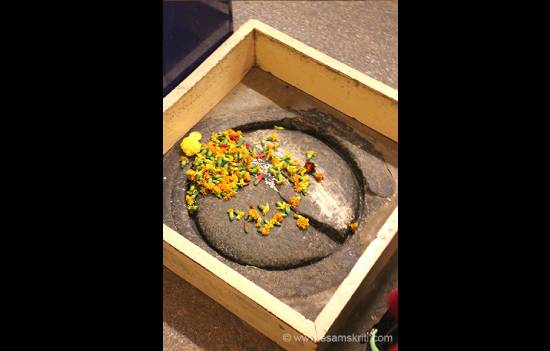

Remains of a Shivlinga inside the temple. 2012.

Remains of a Shivlinga inside the temple. 2012.Around 1590, an itinerant Saivite sanyasi, Mahant Ghamandi Giri, arrived at Bodhgaya and took charge of the Mahavihara. The present Mahant is 16th in the line of succession of Mahants who rescued the Mahavihara and kept the name of Buddha alive in the dark centuries when no priestly or lay community survived to perform the prayers and rituals.

In 1883, Sir Alexander Cunningham, J.D.M. Beglar and Dr Rajendra Lal Mitra renovated the temple on scientific lines. Sir Edwin Arnold, principal of Government Sanskrit College, Poona, during the Mutiny, demanded in 1885 that the temple be handed over to Buddhists; he urged Buddhist countries to espouse this cause. It was classic British divide-and-rule; in 1891, the Anagarika Dharmapala of Sri Lanka jumped into the fray.

After independence, the Bihar Legislative Assembly passed the Bodhgaya Temple Act (Bihar XVII of 1949), which created the Bodhgaya Temple Management Committee, to take care of the temple and pilgrims, and ensure proper worship. The Committee comprised a Chairman and eight members nominated by the State Government, all of whom had to be Indians. In 1953, presiding Mahant Harihar Giri handed over the management to the then Vice President of India, Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan. Since then, the management committee has comprised five Hindus including the District Collector who is chairman, provided he is a Hindu, and four Buddhists.

Now, 77 year old Mr. Wangdi Tshering of Darjeeling has filed a PIL claiming that the Bodhgaya Temple Act is ultra vires Article 25, 26, 29 and 30 of the Constitution. Whatever the merits of his plea, he cannot negate the Hindu contribution in preserving the temple during the darkest centuries when hundreds of sacred temples all over the land were desecrated and even today remain in possession of forces inimical to Hindu dharma.

Mr. Tshering claims the Act violates his Fundamental Right to Freedom of Religion as enshrined in Article 25, which guarantees to every person, and not merely to citizens of India, the freedom of conscience and right freely to profess, practice and propagate religion. He claims Article 25 encompasses the rituals and observances, ceremonies and modes of worship considered by religion to be its integral and essential part. In that case, he will have to prove that the rituals are being violated or compromised by the managing committee.

The petitioner claims that Article 26 gives every religious denomination or section thereof the right to establish and maintain institutions for religious and charitable purposes; manage its own affairs in matters of religion; own and acquire moveable and immovable property; and administer such property in accordance with law. Well, the Gupta rulers who built the great Mahavihara were denominationally Hindu, and the sacred site was in the safe custody of Saivite sanyasis for centuries, until the British instilled the poison of separatism into Buddhist hearts worldwide.

The PIL demands protection of the interests of minorities under Article 29. Ironically, there were no Buddhists in India at all in all the centuries that the temple, its sanctity and rituals were preserved by sanyasis! Nor is relief warranted under Article 30, as the Buddhist community is not establishing the Bodhgaya Mahavihara (which is not an educational institution anyway), but trying to grab it from its historical and civilisational guardians.

As recently as 2005, a Supreme Court bench comprising Chief Justice R.C. Lahoti and Justices D.M. Dharmadhikari and P.K. Balasubramanyan rejected a plea for minority status to the Jain community, saying that the practice of listing religious groups as minority communities should be discouraged. The Court asked the National Commission for Minorities to suggest ways to help create social conditions where the list of notified minorities “is gradually reduced and done away with altogether”, warning that proliferation of minorities would encourage fissiparous tendencies and endanger constitutional democracy. This prophecy is now coming true; we should consider the advice of delisting communities as minorities.

Justices Altamas Kabir and S.S. Nijjar have inadvertently encouraged separatist tendencies nurtured for over a century by colonial agencies and their proxies within the nation. Yet, Hindus have nothing to fear. Undoing the Bodh Gaya Act of 1949 could give them full control of the Mahavihara as The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, will come into operation. And if that Act is struck down, the sectarian plea upheld, and control of the Mahavihara lost, local Hindus can forward claims to Varanasi, Mathura, and myriad temples across the country citing the same precedent. They will not need the support of any political party or all-India organisation.

The author is Editor, www.vijayvaani.com

First published www.vijayvaani.com